Hershel Rich presents Durga Agrawal with a contribution to the India Earthquake Relief Fund.

First Big Ton designed by Ben Tatum and Randy Bailey.

One of PT&P’s first sales agent training sessions.

Piping Technology & Products, Inc., was founded in 1978 by Durga Agrawal. A small company that started in his garage, grew over time into a company widely known as a one-stop-shop for pipe supports, expansion joints, shock control devices, and more. With the invention of the big ton spring and the development of the bolted spring hanger, Piping Technology learned to survive and prosper throughout economic highs and lows over the years. PT&P flourished in the boom of the late 70’s and early 80’s and weathered the economic down-turn that followed in the mid 80’s. Over the years Piping Technology has expanded through the acquisitions of Sweco Fab, Fronek Anchor/Darling, Pipe Shields, and U.S. Bellows.

When arrived Texas in 1969, Durga Agrawal marked the beginning of a journey that eventually would lead him into the world of manufacturing, not in his native India, but rather in the go-for-broke atmosphere of the energy capital of the world…

Preface and Acknowledgements to First Edition

The Piping Technology & Products historical project, in keeping with the spirit of PT&P, truly has been a team effort. As the project historian, I am deeply indebted to a number of people without whose support and participation this project could not have been accomplished. First, this book would not have been possible without the strong commitment of Piping Technology’s founder and president, Durga Agrawal. He selected Benjamin T. Rhodes, Vice President, to oversee the project. Ben Rhodes contributed to the project in a multitude of ways, always with patience and good cheer, and for that I am most appreciative. Also I want to express my gratitude to Jesse Porter who, while performing his regular duties at PT&P, took on the enormous responsibility for doing the formatting, layout, and design of this book. During the summer, R.K. Agrawal brought his insight and computer expertise to assist in the many planning sessions. Bill McDonald and the staff of the Accounting Department on Long Drive were very helpful during the research phase of the project. Finally, I want to thank all of the people of PT&P for their hospitality and support, and especially the individuals who agreed to be interviewed for this history. Their contributions proved invaluable to the writing of this book, and also will provide a permanent oral record of the history of the company.

In addition, there are several people outside of Piping Technology to whom I am indebted for their efforts on behalf of this project. Suzanne Mascola transcribed all of the oral history interviews in her usual professional and timely manner. Sethuraman Srinivasan, Jr. worked throughout the summer as the project research assistant. He surveyed PT&P’s vast photo collection and organized a catalog from which we selected the illustrations for this history. In addition, he helped assemble background information, developed photo essays, wrote captions, and provided many useful ideas for the book. Finally, I want to express my gratitude to Dr. Joseph A. Pratt, NEH-Cullen Professor of History and Business at the University of Houston. As the project director, he brought his expertise as a business historian and his editorial skills to help guide this study to its completion.

Preface and Acknowledgements to Second Edition

Dr. Durga Agrawal, founder and president of Piping Technology & Products, Inc. (PT&P), contacted me during 2008 to discuss writing an update to the original history of the company that I had completed in 1998. Over the years, I kept track of PT&P and thus was delighted to be asked to write a sequel about this very interesting and very successful Houston firm. As I began my research, I found a company that had grown in size and matured as an organization, but remained true to its mission and corporate ideals.

Several themes carry over from the first edition, including the strong emphasis on quality and testing of PT&P’s products. A major extension in those themes is found in the push for professionalization at the company. Not only did quality control still matter, but the emphasis was on attaining formal industry recognition and certification of the standards that PT&P met or exceeded. The company matured as a business in other areas including its use of computer technology, the development of its website to include features that made it an information resource for the piping industry, and steps to improve in plant safety. Thus, while history necessarily is about change over time, the changes at PT&P since 1998 have been contributing factors to the company’s successful expansion of its product line and production capabilities, and its consequent success in gaining new customers, competing in new areas for business, and in securing the largest projects in the history of the firm. PT&P grew from being a reliable provider of pipe hangers and pipe supports to a “one-stop-shop” for a wide variety of engineered products and services for the piping industry.

This new edition of PT&P’s history builds upon the first book originally published in 1998. The original six chapters have been slightly edited but contain essentially the same information about the first twenty years of the company’s history. The new edition has four additional chapters that examine the growth of PT&P as a business and its expansion into new product lines during its third decade. Chapter seven looks at the impact of PT&P’s acquisition of U. S. Bellows and the use of new technology as a tool for marketing and communicating with customers. Chapter eight explores the company’s entry into enhanced engineering services, opportunities in the merchant power plant arena, and the important acquisition of the Fronek Companies from Shaw Group. Chapter nine focuses on a maturing firm and the opportunities it provides for employees, certification of its quality control programs, and enhancement of plant safety. The final chapter provides an overview of the impact of the company’s growth in the industry and the subsequent opportunities the success of the firm presented to its founder, Durga Agrawal, as a business leader and in community service. The story of this company is a classic story of the American Dream coming to fruition, and it also is an excellent case study of the growth of a successful, small-business, fabricating company through the economic cycles of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Once again I am grateful to Dr. Durga Agrawal for his commitment to recording the history of Piping Technology & Products. Randy Bailey, Vice President, was very gracious in offering his time and support to talk about the company and the significance of its expansion over the past ten years. Helen Conol Villaruel, Agrawal’s executive assistant, helped in countless ways by providing documents and other printed information, and in scheduling oral history interviews. Dr. Ben Rhodes, the now retired former vice president, provided his expertise in a careful reading of the manuscript, and for his help I am deeply indebted. I also wish to express my gratitude to the people who made time in their busy schedules to participate in oral history interviews, without which this project could not be completed. Their names appear in the Note on Sources at the end of this book. Suzanne Mascola transcribed the interviews, Aarati Agrawal contributed several ideas for the manuscript, and my long time associate, Kimberly Youngblood, provided research and editing assistance throughout the project. Finally, to all the people of PT&P— my thanks for your gracious hospitality and support for this history project.

Introduction

Piping Technology & Products, Inc. (PT&P) is one of the leading manufacturers of pipe supports and other piping products in the world. This book is the story of how the Houston-based company grew out of a small engineering consulting firm to take a prominent place in the piping industry. The company’s founder, Durga Agrawal, first came to Texas in 1968. A young college student from the small village of Lakhanpur, in central India, Agrawal had planned to complete his graduate studies in engineering at the University of Houston and then return to India to establish a business. Although he did not know it at the time, his arrival in Houston marked the beginning of a journey that eventually would lead him into the world of manufacturing, not in his native India, but rather in the go-for-broke atmosphere of the energy capital of the world—Houston, Texas.

When Durga Agrawal first established Pipe Technology & Products, Inc. in the summer of 1978, he sought to create a niche for his company in the pipe support industry by providing fast, dependable service for his customers. He accomplished this primarily by developing innovative designs that improved the company’s line of products and made the firm’s production methods more efficient. This enabled Agrawal to reduce the extended lead time—that is the amount of time required for products such as spring hangers to be manufactured and delivered—that had been the rule in the days before PT&P. Agrawal’s innovative approach to the piping industry and his willingness to diversify into new areas of manufacturing enabled his small company to survive and prosper in a highly competitive environment. Later during the mid-1980s, when Houston’s economy crashed with the demise of oil, gas, real estate, and petrochemical industries, PT&P, like other industry-dependent companies, found itself in a struggle for survival. Yet, while many competitors saw their business fail, PT&P not only survived but also thrived during the economic downturn. How then did this upstart business out-maneuver its competitors in a way that enabled the company to survive Houston’s economic “bust” of the 1980s and become one of the leading manufacturers in the piping industry?

Several critical elements worked together in Agrawal’s favor as he began his quest to get the fledgling company off the ground. During 1978, Agrawal’s firm went through a reorganization that involved a transformation from consulting to manufacturing and fabricating business. The company had booked enough substantial work to allow Agrawal to bring in key people on a full-time basis. As a result, PT&P had a new sense of direction and the people to enable the firm to compete in the market place. In addition, the timing and the location for this venture—in the midst of the 1970s oil boom in Houston, Texas—could not have been better. In order to understand the significance of PT&P’s success and survival and to place the story of the company in its proper historical setting, it is useful first to examine briefly the backdrop for the endeavor, the economic climate of post-war Houston.

During the years immediately before World War II, Houston’s oil, gas, and petrochemical industries began to thrive. By the end of the war, these industries expanded to such an extent that the city became known as the “energy capital of the world.” Because of its close ties to the oil industry, Houston was able to avoid the severe economic downturns that plagued other regions of the country during the post-war years. The phenomenon was due to the counter-cyclical upswings that the oil or energy-based sector experienced just as other areas of the economy went into their slumps. One of the best examples of this occurred during the early 1970s. Just as the national economy began to experience a major recession, the Arab oil embargo in 1973 brought a huge increase in oil prices that gave Houston’s economy an immediate boost. Crude oil prices shot up—quadrupling in just 90 days. With the price of oil closing in on $38 a barrel, the search for oil—which had become prohibitively expensive due to low oil prices—became economically feasible once again. The increase in oil prices stimulated an increase in oil exploration and drilling. The domestic oil rig count—a barometer of oil field exploration activity—rose from around 1,000 active rigs to 1,472 in 1974, 1,660 in 1975 and over 2,000 in 1977. When oil prices increased again in 1979, the rig count jumped again climbing to 4,250 by the end of 1981.1 Although the rising oil prices deepened the national recession, the initial impact proved beneficial to Houston-based manufacturers. The firms that produced oil field equipment and supplies along with those who provided oil field services and energy technology saw a huge leap in revenues. The ripple effects of the new energy boom quickly spread throughout the Houston economy. Among the beneficiaries of the boom were those companies that provided products like pipe supports, pipe hangers, and expansion joints for the downstream sector of the energy industry—oil refineries and petrochemical factories—including Piping Technology & Products.

During Houston’s fabled economic boom of the 1970s and early 1980s, the city experienced tremendous growth in population, employment, and income. In 1981 the population grew 7.2 percent, employment rose 8.4 percent, including 167,000 new jobs in oil field equipment manufacturing, and personal income shot up an incredible 19.9 percent. Since all these occurred during the time of a sagging national economy, it appeared certain that Houston was experiencing yet another of the city’s historical counter-cyclical booms. Oil prices continued to rise and many experts confidently spoke of benchmark surpassing $50 per barrel. All of this led city officials and business leaders to believe that the prosperity would continue into the foreseeable future, bringing economic growth and expansion during the rest of the decade.

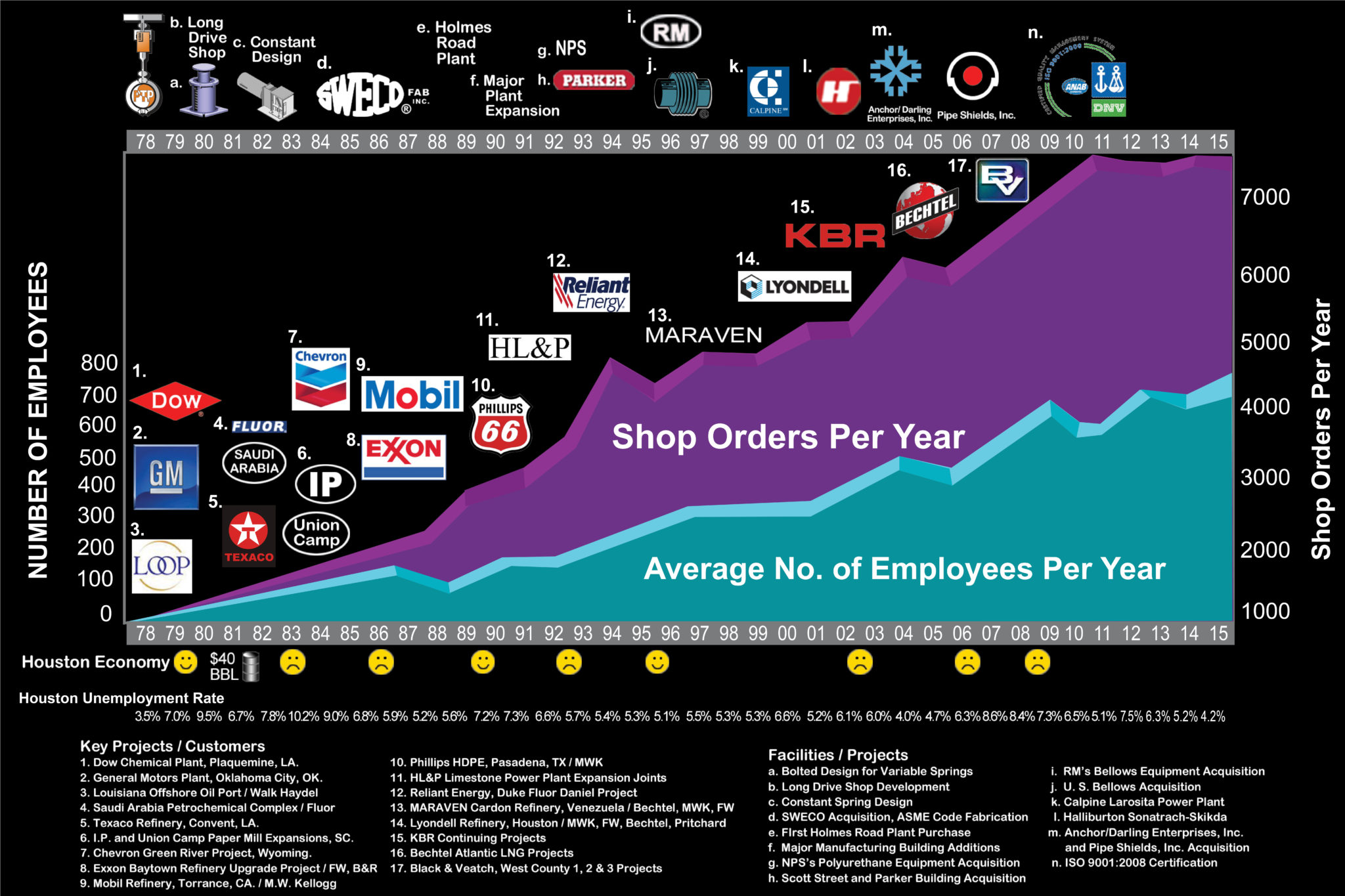

The revitalized oil industry seemed to possess an insatiable demand for a variety of manufactured products including piping, oil rigs, and new valves and instruments. Increased orders for new piping meant an increased demand for other piping products. Durga Agrawal established Piping Technology in 1978, just in time to take advantage of this furious activity in the petrochemical industry. By 1981, PT&P had begun to catch the crest of this wave of prosperity and saw the number of shop orders-per-year leap from 51 in 1978, to 819 three years later. But late in 1981, PT&P’s management—Durga Agrawal, Randy Bailey, and Terry McCormick—saw the signs of an approaching slowdown. The larger engineering and construction companies had stopped announcing major new jobs. Some had begun to furlough their employees, slowly at first, but the trickle soon grew into a flood of massive layoffs.

During 1980 and 1981, the national economy began to slide into one the worst declines since the Great Depression. Because Houston’s economy was stronger in 1981 than in any of the preceding twenty years, its abrupt decline in the spring of 1982 left most business and community leaders in shock. Increased world production of oil, conservation of energy spurred by higher prices, and a worldwide recession during the early 1980s changed the dynamics of the oil business by creating a worldwide oil glut. OPEC lost its power to set prices, domestic production dropped, and the economic incentive to drill, especially for high-cost oil, began to disappear. The result was a significant decline in the number of oil rigs actively used for drilling. With this decline came decreases in new orders for all types of oil field equipment and services. Within eighteen months, the Houston economy lost 100,000 jobs. The city once considered recession-proof soon saw its unemployment level exceed that of the entire nation. As a result, the ripple effects of the big downturn created havoc for businesses, for the financial community, and for the public sector. By 1986, Houston’s unemployment rate had climbed to 10.2 percent, while national unemployment stood at 6.9 percent. In manufacturing alone, the number of jobs plummeted by 33 percent from the 1982 peak. In fabricated metals, PT&P’s sector of the economy, the number of jobs dropped by 40 percent. In electronics, it fell by 43 percent, and in non-electrical machinery by 50 percent.

The cause of the sharp downturn in the Houston economy is more complex than simply oil prices. A regional economy like Houston’s is comprised of two segments: the primary sectors, which are often referred to as the economic base, and the secondary sectors. The businesses that make up the primary sectors are the driving force behind the economy and produce goods and service for export out of the region. The secondary economy, which provides goods and services to the local communities, relies upon the continued growth of the primary sector. Although there was some diversification—the development of the Texas Medical Center and NASA’s Johnson Space Center—Houston’s economic base depended upon the prosperity of one industry. The Greater Houston Partnership, an organization that grew out of the Chamber of Commerce’s efforts to bolster the economy, explained the problem in a 1989 report: “The fact that 84 percent of the area’s economic base is related to exploration of oil and natural gas and to the production of fossil fuel products mean that 84 percent of all employment is either directly or indirectly tied to these energy industries. Roughly 84 percent of all grocery clerks, auto mechanics, real estate agents, and schoolteachers owe their jobs to the energy sector. Without the energy sector Houston would be a city of about 500,000 only the third largest in Texas.5

When the oil boom began to break in the spring of 1982, the economic base stopped expanding and by 1985 had fallen into a prolonged period of severe contraction. Many small businesses in Houston, including a host of manufacturing and fabrication companies, had relied heavily upon the continued growth of the energy-dependent industries. When that growth stopped, the big petrochemical firms delayed or cancelled plans for new construction projects and plant upgrades. This left companies like PT&P that had based their futures on supplying their products for petrochemical plants, with no new business and very bleak prospects. If oil exploration had merely leveled off during the 1980s, Houston’s boom would have slowed substantially. Instead, U.S. exploration fell by almost one-half, devastating Houston’s economic base and spreading quickly to the secondary economy.

Houston’s boom and bust shaped the history of Piping Technology & Products in a dramatic way. Although the Bayou City had been one of the best locations in the nation in which to start a business, the sudden demise of the “boom” in 1982 should have meant disaster for PT&P. But this was not the case. In fact, when the economy began to bounce back in 1988, PT&P emerged from the malaise in position to take a leading role in the piping industry. The history of PT&P, then, is the story of how dedication, innovation, and determination enabled this company to overcome many obstacles, including the economic catastrophe that hit the city in 1982, to become one of Houston’s successful entrepreneurial endeavors.

This book is a chronicle of Piping Technology during its first twenty years. The story is told in six chapters dealing with important eras in the company’s history. First, the book provides brief background information about the company’s founder, Durga Agrawal, the origins of the firm as an engineering and consulting partnership, Stress Technology & Products, and the transformation into PT&P. Chapter two explores how Agrawal took advantage of the oil boom in Houston to turn his fledgling enterprise into a profitable manufacturing concern and introduced a new design for variable spring hangers that revolutionized the pipe support industry. In the third chapter, the book examines how PT&P survived Houston’s economic slump (1982-87) through aggressive marketing in new areas and through “intelligent diversification” into complementary areas of manufacturing including the acquisition of SWECO. Chapter four describes the move to PT&P’s present headquarters on Holmes road and the acquisition of equipment that allowed the firm to continue its diversification into cryogenic pipe support and expansion joint manufacturing. As the company continued to grow from a small business into an important supplier of piping products, the need arose for PT&P to modernize its information management systems, adopt standardized procedures, and upgrade many facets of its operations. Chapter five, then, looks at the development of the company’s in-house computer programs, the application of computer technology throughout the plant, and the evolution of other, more traditional management concepts. Finally, chapter six examines recent milestones in the company’s history.

Durga Agrawal assembled a ground of talented people to help him operate his company, and together they steered a course through the myriad obstacles they encountered during the early years of PT&P. Now, after its first twenty years, Piping Technology & Products stands as one of the leading manufacturers in the piping industry.

city of Houston, attracting students from all over the world. This building was completed in 1967, was a major addition of classrooms, offices and laboratories.

city of Houston, attracting students from all over the world. This World War II vintage metal building was used for laboratories and

offices for graduate students.

Chapter 1: Laying the Foundation: 1975-79

“Our timing was great really” says Durga Agrawal. “Around the time we started doing stress analysis, the economy was booming. Everybody was talking about petrochemicals. There was so much work going on…everybody was asking people in Houston to do their design work and contractors from Houston were doing work all over the world.” The mid-1970s was a great time to establish a business in Houston, Texas, especially a business connected to energy-related industries such as petrochemical. The Bayou City was known as the energy capital of the world, and the petrochemical industry was one of the driving forces behind a wave of prosperity that had washed over the entire region. Throughout its history, Houston had been a great place for bold entrepreneurs to take their chances that a new idea, a new service, or a new product might bring them success and prosperity. In this setting, Durga Agrawal parlayed his manufacturing experience and the advanced engineering skills he had acquired in six years of graduate school into a profitable engineering and consulting business. In 1975, he entered into a partnership to establish Stress Technology & Products (ST&P), a consulting firm that within the next three-years, evolved into a manufacturing and fabrication business. In 1978, however, the original partnership dissolved and a new company, Piping Technology & Products emerged with Durga Agrawal at the helm.

Agrawal assembled a core of talented people including Randy Bailey, Ben Tatum, and Art Usher, to help him launch PT&P after the reorganization of 1978. During the ensuing years he continued to bring new people into the organization, as the need for additional help became apparent. The rapid growth of Piping Technology during the first four years of the company’s history was due primarily to management’s success in product development, marketing, personnel recruitment, and in locating reasonably priced, used, manufacturing equipment. Agrawal and Randy Bailey pursued all kinds of pipe support business, booking every job possible, both large and small. While the increasing flow of business brought a corresponding increase in the company’s revenue, it also brought a wave of growing pains that challenged the resourcefulness of the entire staff. The rapid pace of business rarely left enough time to sit down and work out a growth strategy. But, Agrawal possessed an innate business sense and his enthusiasm for PT&P was contagious and inspired those who came on board with him to stick it out through the good times and the bad. What emerged from these rather chaotic beginnings, then, was a stubborn little company with a small but dedicated staff intent on making the business a success.

Agrawal’s entrepreneurial heritage can be traced back to his family’s business in the small village of Lakhanpur, in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. Although he lived in a small village, Agrawal grew up steeped in the lessons of India’s business class. His father owned a fabric shop that grew into a kind of general store that he operated as a wholesaler, retailer, and general merchandiser. Young Agrawal helped his father during busy afternoons by calculating the customer’s accounts in his head. “Yes, I learned a whole lot about the business there, you know, because that is all I had seen since early childhood. I would help my father all the time doing accounting. Even when I went away from high school, when I came home for holidays…I would be helping in the shop again. So that is where I got the business background.”

Lakhanpur during Agrawal’s youth was a small village of about 900 people. There was no railroad, no electricity, and no water supply. “We used to light kerosene lamps for reading,” he said. The Agrawals were a deeply religious family and raised their seven children—Durga along with three brothers and three sisters—in the Hindu faith. Many of his fondest memories are of those occasions when the family gathered together to celebrate religious holidays. Here he developed his devotion to family and his deeply held religious convictions. As a child, Agrawal enjoyed competing in sports—especially volleyball and soccer. In school he was an excellent student with an affinity for mathematics.

In those days Lakhanpur was too small to have a high school, so Agrawal moved to the nearby town of Ambikapur, about an hour’s drive to the northeast, to complete his schooling. Here he followed a course of study that emphasized math, chemistry and physics. Agrawal graduated at the top of high school class and earned a gold medal in recognition of his academic achievements. But in 1962, war broke out when China attacked India and the country needed every ounce of gold to buy military supplies. Consequently, Agrawal and other students of the class of 1962 never received their medals.

Still, he had earned a scholarship to attend the Delhi College of Engineering in New Delhi. He studied mechanical engineering and gained extensive practical experience while training in one of the factories owned by the Indian business conglomerate, Tata. Agrawal graduated from the University of Delhi with a Bachelor’s Degree in 1967. During his final year of college, he decided to apply for admission to graduate school in the United States. As he later remembered, “I sent letters to a lot of universities and got admission into two or three places. One of them was the University of Houston. Many of my friends—four or five of the other guys that I knew—were coming here from Delhi, so I decided to come here. And the plan was to get a Master’s Degree and go back and do something in India…help my father in his business or get some kind of industry started there.”

<pclass=”norm”>When Agrawal arrived at the University of Houston in January 1968, most of the graduate level classes were already full, but he was able to enroll in a course taught by Dr. Benjamin T. Rhodes, an Industrial Engineering Professor. Rhodes later recalled their first meeting: “Durga came as a graduate student, majoring in Industrial Engineering. He was one of the first students that we had from India and was obviously a bright, energetic guy. I was teaching a graduate course in Reliability, which was really designed for the engineers at NASA. And because he came at mid-term, I guess he didn’t have a whole lot of choices of what classes he took, so his first semester in the U.S. he was in one of my classes.” Rhodes became Agrawal’s academic advisor and years later, when Agrawal needed help managing his growing business, he called upon his friend and mentor, Ben Rhodes, and asked him to come to work at PT&P.

During the summer of 1968, Agrawal took a part-time job at the Phil Rich Fan Manufacturing Company. Phillip Rich, a Russian immigrant, established the company near the end of World War II. Later, he turned the day-to-day operations of the business over to his son, Hershel, a formal naval officer and engineering graduate of the Rice Institute in Houston. Hershel Rich built the company into a successful fan-manufacturing firm before selling the business to the Sunbeam Corporation in 1981. He remembered Durga as someone who “caught onto everything very quickly…a good problem-solver. He worked on manufacturing processes and automation. He was very observant and was very interested in every aspect of the business.” Agrawal eventually became the firm’s chief engineer. Among the projects that Agrawal worked on was a special design for fans sold to the Defense Supply Agency (DSA) for use by the Navy. He also came up with a design that lowered the cost of the fan by substituting a specially designed gear mechanism with plastic and nylon gears for the brass gearbox. Agrawal’s design eventually helped the company to secure a major contract with the DSA.

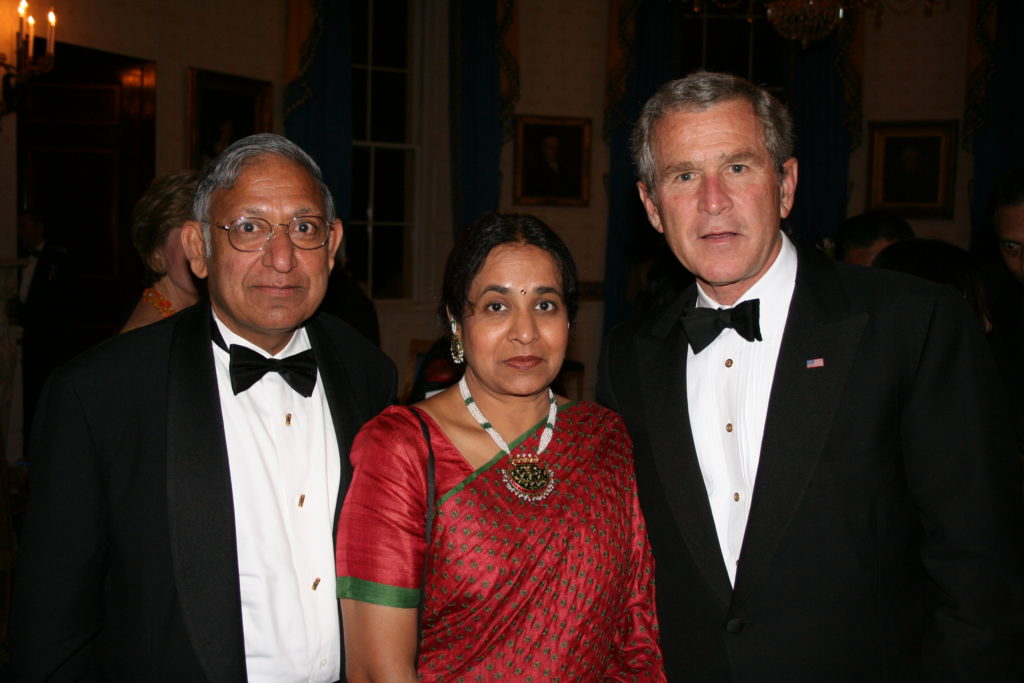

Durga Agrawal and Hershel Rich maintained a close friendship during the years after Durga left the Phil Rich Fan Manufacturing Company. Here in 1990, Rich presents Agrawal with a contribution to the India Earthquake Relief Fund.

During the time he worked at Phil Rich Fan, Agrawal met a number of people whom he later brought into PT&P. One of Agrawal’s co-workers there was Ben Tatum. A Louisiana native, Tatum migrated to Houston in 1956. He had gained extensive manufacturing experience working for several small fabrication companies before going to the Phil Rich Fan Company in 1957. Tatum, who eventually became a shop foreman, recalled the days at Phil Rich Fan saying “Actually, that is where I got to know Durga originally. Durga came to work there as an engineer and was basically in charge of Engineering and Special projects.”

Agrawal worked there while he continued his graduate studies in the University of Houston. Shortly after he received a master’s degree in industrial engineering, while he debated where he would pursue his goal of earning a Ph.D., Agrawal received a call from his family in India. They summoned him home to meet a young lady whom they had identified as a prospective bride. Following Indian custom, the families had discussed the possibility of marriage of the two young people. Once the brides family had met Durga and indicated their approval, he was introduced to his future wife, Sushila. The young couple could have vetoed the marriage, but both decided that the relationship had great promise. They married in New Delhi in January 1971 and returned to Houston to set up their home and begin their life together. Sushila Agrawal had no idea what to expect when she came to Houston. She said years later. “You know, you feel out of place for a while.”

After he returned to Houston, Agrawal continued working at Phil Rich Fan, and deliberated whether to complete his Ph.D. or pursue his engineering career. After all, he did have a new wife and soon children would follow. After many long discussions, Sushila convinced him that since he had completed all of the course work, he ought to finish his dissertation. Agrawal left the fan company and took a part-time job with Comfort Supply Company while he continued his academic work. In 1974, Durga Agrawal received his Ph.D. in engineering.

Chapter 2: Developing a Business: 1979-81

Innovation and customer service enabled PT&P to carve out a niche in the pipe support industry. The development of the “Big Ton” provides an interesting illustration of this. Andre Hydel of Total Petroleum contacted PT&P and asked for a way to support a large vessel that would be both stable and economical. Ben Tatum and Randy Bailey responded by designing the big ton, essentially a table atop muscle springs. Total Petroleum was so pleased with the design that they gave more business to PT&P and found other uses for the Big Ton.

“Well, I think the story of the bolted design for variable spring hangers is a very significant milestone and so that’s a story that needs to be told. Even after the idea hit [Durga Agrawal], it probably took him a while to implement it. And then, it took him a while to realize that it wasn’t just a quality improvement, it was a way to build a different kind of manufacturing system which had a real competitive edge.” Ben Rhodes, Vice President of Piping Technology & Products, is among the many PT&P officials who believe that Durga Agrawal’s bolted design spring hanger has been one of the most important factors in the company’s overall success. Agrawal’s revolutionary new design substantially improved the quality and durability of the product, but more importantly, his concept of using interchangeable parts and mass production techniques gave PT&P a competitive edge that the company’s rivals found very difficult to overcome. The bolted design spring hanger turned out to be Agrawal’s ace-in-the-hole during company’s formative years. It allowed him to produce this crucial, high-demand product at a much lower cost than his competitors. Consequently, as PT&P became better known to the major engineering and construction companies, Agrawal’s team was able to submit competitive bids and win many of the most lucrative contracts during the late 1970s and early 1980s. These jobs made PT&P a contributor to some of the most prestigious and significant construction projects of the era.

While increasing the flow of business brought a corresponding increase in the company’s revenues, it also brought a wave of growing pains that challenged the resourcefulness of the entire staff. The rapid pace of business rarely left enough time to sit down and work out a growth strategy. PT&P’s strategic growth plan essentially was to keep booking orders and deal with the exigencies individually as they came along.

While they may not have developed a formal growth plan, Agrawal and his team refused to be overwhelmed by the tasks and challenges of a very competitive marketplace. In this way, more by process than by design, PT&P grew into a major supplier of pipe supports and related products. All of this did not just happen, of course, but in meeting the challenges and crises that ultimately face most small businesses, PT&P took advantage of the booming economy to augment its share of the market and in the process, reinvented itself as a viable business organization.

The first crucial step was to create a niche for the company in the piping industry. For PT&P, this meant finding ways to improve the quality of key products and provide faster and better service to customers than the competition. Second, the company had to hire additional personnel, both in the shop and in the front office, qualified people who could organize the various functions of the business and keep the company growing and maturing as a reliable manufacturer of pipe supports and products. Third, PT&P had to purchase equipment to expand its manufacturing capabilities.

All of these developmental steps took place more or less simultaneously. One of the first and clearly most significant steps involved the development of a new kind of engineered spring hanger. This product helped PT&P in its quest to carve out a specialized niche and compete effectively with older more established firms. The bolted spring hanger became one of the company’s most important products and a mainstay of the PT&P catalog. As the name suggests, a spring hanger is a device used to suspend piping, to hang it from steel beams in a manufacturing plant, refinery, or other location. Each spring support is individually calibrated to the various pipe loads and movements specified. During the early 1970s, spring hangers were “like gold” to piping engineers, in part because of their vital role in the piping system, but also because they took a painfully long time to manufacture. Orders for spring hangers required a “lead time” of as long as six to eight weeks, because they had to be customized to meet the buyers’ specifications and then individually manufactured. This meant that customers had to place orders weeks ahead of the time they were needed so that the installation of the piping could go ahead on schedule. Delays caused by tardy delivery of spring hangers meant that the piping could not be installed and this often caused entire projects to fall behind schedule.

The manufacturing and assembly processes were difficult and very labor intensive. Frequently, special coil springs had to be ordered to meet specifications that required certain sizes and spring rates. In addition, other materials for the rest of the spring hanger assembly had to be purchased and brought in. To fight corrosion, purchase orders usually specified a hot dip galvanizing treatment for spring hangers. That meant that that the canister or can had to be built, sent out to be galvanized, and then returned to the shop for final assembly. This too was a time consuming and tedious process. To install the coil spring inside the can, the spring had to be compressed in a hydraulic press with a load ranging from 50 to 50,000 pounds. A welder would actually weld the end of the can shut while the spring coil was held compressed. But this process created a new problem. Although it was not apparent during the assembly, by welding the pieces after they had been galvanized, the welder actually burned the galvanizing off, which made it susceptible to corrosion again. Randy Bailey noted that, “When you welded it shut after it was galvanized, it always corroded later. It always rusted at that spot…everybody did it that way.” The welding created another problem that could not be seen by quality control personnel. The coil springs were coated with neoprene to prevent corrosion and the subsequent failure of the spring hanger. The welding process frequently melted or otherwise damaged the thin neoprene coating on the springs inside the canisters.

Chapter 3: Thriving Through Diversification During Houston’s Economic Downturn

“None of the operating companies were mounting new projects,” said Terry McCormick. “Because, you know, the price of oil was going down and they were going through their massive layoffs. Every major company was cutting back.” During the 1970s and early 1980s, business opportunities abounded in Houston and the entire city seemed awash in money. Rising oil prices fueled the boom which stimulated business in all sectors of the city’s economy. Then suddenly, in 1982, it all began to sour. By 1985, the boom had turned to bust, causing many businesses to fail and many people to lose their jobs as those firms that relied upon energy related businesses laid-off employees and closed their doors. The Bayou City suffered through five years of economic contraction with some areas feeling effects more traumatic than during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Although it may have seemed like it at the time, all of Houston did not fold during the economic downturn of 1982–87. Many companies survived the energy recession and some found themselves in better condition by the time the Houston economy began to turn around in 1988. One of those companies was Piping Technology & Products. The company was strong enough to weather the most severe downturn in the recent history of the oil, gas and petrochemical industries without the “downsizing” that many firms endured during those difficult days.

There are a number of reasons for the remarkable survival of Piping Technology during this difficult time. Unlike many Houston firms, PT&P had not mortgaged its future by borrowing heavily to finance expansion or capital improvements. Also, with the large contracts to provide pipe support products for the Texaco refinery in Convent, Louisiana and the giant Saudi Arabia Petrochemical Complex at Al-Jubail, PT&P had two long-term projects to carry the company for a while. Finally, Durga Agrawal, Randy Bailey and Terry McCormick had seen the downturn approaching as early as 1981 and began to search for alternative markets. They saw a need to diversify the company’s customer base and to expand their product line. Consequently, the company continued to book jobs and continued to grow throughout the period of the downturn. By the time that both the local and national economies began to recover somewhat in the late 1980s, PT&P had moved to a larger facility, acquired a new subsidiary, SWECO, and added new manufacturing capabilities while, during the same time, many of their competitors had been forced to close their doors.

Terry McCormick talked about the big economic crash years later. He recalled the drop in oil prices noting, “If you looked at August of 1982, West Texas Intermediates were trading for $39 a barrel. Four years later, in August 1986, they were trading for $9.50 a barrel, and 245,000 people had lost their jobs in Houston in that four year period.” The falling oil prices meant a decline in revenues for the oil companies. Among other things, this delayed plans for new construction and upgrades of existing refineries and other facilities. With little of this type of work being awarded, the big engineering and construction companies began reducing their workforces. McCormick recalled that “Fluor Corporation here went from like 3,900 people to 450 people. Bechtel was flat. Lummus was flat. Brown & Root was flat. Everybody in town was flat. The only thing that wasn’t flat was Fluor [California] and that was by virtue of this big job in Saudi Arabia. The only thing that C.F. Braun was doing was their portion of the job in Saudi Arabia. So, no new jobs were being awarded and it was a very, very critical period of time.”

PT&P continued to pursue work but in reality, there was not much work to pursue. McCormick utilized this slow period to bolster his contacts and keep in touch with the people and the companies that PT&P had done business with previously. He dropped in at the engineering companies to chat with the piping and stress engineers who still remained. The slowdown provided “a wonderful opportunity to call on those people…they were very receptive to meeting you.” All of this generated good will and would pave the way for PT&P to be assured of receiving inquiries once the economy picked up and the engineering and construction companies began getting new projects.

One of PT&P’s first sales agent training sessions.

In addition to shoring up PT&P’s contacts with the engineering and construction companies, McCormick began putting together a network of sales agents to represent PT&P in other parts of the country. Usually these agents were independent businessmen, manufacturer’s agents who represented three or more companies. Whenever McCormick traveled, he contacted the local agents and they would make calls together, visiting potential clients to make PT&P known to them. “So, that gave us an opportunity to call on the engineering companies, those that we were doing business with and those we hoped to do business with, and it gave us an opportunity as well to call on the major operating companies. Our [agents] have played an important part in our growth over the years.” Eventually, PT&P established a worldwide network of manufacturer’s agents to represent the firm.

During the early 1980s, PT&P had begun looking for ways to diversify and expand into the non-energy-dependent sector of the economy. Durga Agrawal briefly considered the idea of getting into the computer business as an after-market reseller. Although he did not aggressively pursue that option, diversification clearly was on his mind. As he recalled later.

“We started seeing the downturn coming a year before it happened,

or a year and a half before it happened. I knew that the petrochemical

business would be down the next two or three years. That’s when we

started planning to diversify and get into other areas like building

expansion joints for the highways, doing anchor bolts, slide plates, all

kinds of miscellaneous steel fabrication, including getting into wastewater

treatment plants. So, we started focusing on those smaller, labor-intensive

jobs. And because of that, we kept everybody busy. We didn’t have to lay off

anybody. We kept on expanding. We kept on hiring more and buying more

equipment also.“

PT&P was willing to try almost anything to keep the business going and to keep its employees working. As a result, the company not only survived, but also the expanding capabilities actually helped propel the firm into a new growth cycle. Randy Bailey described the period noting that, “Every year, we almost doubled in size, because we looked for diversification or options. In fact, that is when they passed the Clean Water Act and companies started doing a lot of wastewater treatment facilities. We branched out and we started working on sewer treatment plants. And so, we would go wherever they needed pipe, wherever they had pipe supports.” The growing use of personal computers during the 1980s led to a corresponding demand for computer paper, which led to a boom in the pulp and paper industry. “They had a big push in the paper mills because they had so much [demand for] computer paper,” said Bailey. “So, all the paper mills had to expand to keep up with the need and that’s when we supplied all the hangers to the paper mills.

Chapter 4: A New Era: The Expansion of the 1990s

In 1993, the Houston Museum of Natural Science presented PT&P with one of their most unusual challenges. The Museum planned to add an exhibit on pipelines and asked PT&P to fabricate an exhibit that allowed visitors to experience what it was like to flow inside a pipe. Bob Sonier, SWECO’s top designer (pictured at the exhibit with Randy Bailey and Durga Agrawal) took up the challenge. The resulting museum piece is still on display.

“We had grown about as big as we could grow over there,” said Ben Tatum. “So, we looked at several facilities…and we settled on this piece of property. We thought it suited us real well and it would take care of our long-term growth plans, and basically, we felt like we had enough building space and floor space to accommodate us for some time to come. As it turned out, within less that two years, we found that we really didn’t have enough space here either because of the way the company was growing.” PT&P continued to grow during the 1980s and into the 1990s primarily due to the company’s ability to adapt in a changing economy, to diversify its catalog, and to find new areas in which to market its products. Consequently, while many small firms in the piping industry went under, PT&P saw its business steadily increasing to a point where, as Durga Agrawal recalled, “Well, we got crowded. There were no parking places, people were stepping on one another…we couldn’t find things. That is when I started looking for a place where we could have more space.” One of his projects during his return from India for the summer months in 1988 would be to find a new facility for his growing manufacturing concern.

Besides the overcrowding on Long Drive, other issues had begun to arise that threatened the continued growth and long-term health of his company. The recently acquired SWECO facility on Texarkana Street also began having problems. First, the building was in need of extensive repairs. Second, since Houston does not have zoning laws, businesses are often located in the middle of residential neighborhoods. This was the case with SWECO, which was near an area of homes occupied by families. Ben Rhodes remembered an incident in which the company found itself on a tight schedule to produce a substantial number of small pressure vessels for Bechtel. “The way we planned to meet the schedule was by having a second shift,” he said. “With all these grinders and so on going on at night, the neighbors said, “Our babies can’t sleep.” So, the police came out and…anyway, they convinced us we should not do this.” In addition, because of the overcrowding, SWECO had rented space from Wilson Industries, a firm located near downtown Houston. This made a busy workday even more hectic for PT&P’s management and workers alike. “So now, we had three shops—Long Drive, SWECO on Texarkana, and one more shop,” said Ben Tatum. “And that became really inefficient. People had to travel to three places and so it made sense to find a place where everything could be together.”

PT&P had already acquired two adjacent parcels of land on Long Drive. By 1988, there was no land available into which the firm could expand. Agrawal launched a city wide search for a suitable facility and quickly found several options to choose from. Here again, timing played a crucial role in the growth of PT&P.

Chapter 5: A Continuing Process: The Modernization of the 1990s

Piping Technology & Products found itself in a time of profound change as the 1980s flowed into the 1990s. The company had survived the difficult economic slump of the 1980s through continually reinventing itself. By the end of the decade PT&P had a new home and was poised to embark on the greatest period of expansion in the firm’s history. But first, PT&P would have to address a number of administrative and systematic growing pains that threatened the company. In particular, PT&P needed to incorporate the latest developments in computer technology to standardize procedure in a way that would streamline the firm’s operations. Also, it had become necessary for the company to reinvigorate its marketing ability with an update of its catalog and brochures.

Although Durga Agrawal made several trips to India between 1986-1991, he was never out of touch with his company in Houston. He communicated daily by telephone and traveled to Houston about every six weeks, In addition, he had brought in Dr. Ben Rhodes, his former college professor and graduate advisor, as one of the firm’s vice presidents. While Randy Bailey managed the day to day operations, one of Rhodes’ missions was to take a broader view of PT&P, thinking strategically about the firm’s future as a viable business entity. Now, Agrawal, and his management team—Vice Presidents Randy Bailey and Ben Rhodes, Controller Ellsworth Seaman, Sales Manager Terry McCormick, Operations Manager Larry Altshuler, and Plant Manager Ben Tatum—would begin an internal transformation of PT&P that would help to modernize the firm’s operations and place the company in the forefront of its area in the piping industry.

After he joined the firm in September 1986, Rhodes initiated a series of “manager meetings” to provide a forum in which PT&P officials could raise issues, express concerns, and offer suggestions that would address the needs of the company. These meetings spawned a number of subcommittees to look into issues facing the company and to formulate strategic plans for the future. Issues raised included the acquisition of new computer technology to help manage more efficiently the growing company. In addition, the company embarked on a process of streamlining, standardizing, and modernizing that would make PT&P more efficient and even more competitive. Central to this was the company’s embrace of computer technology for every department.

Still, Smith and others observed that an inordinate amount of repeated data entry slowed the processing of orders. Smith also noted a pattern. As PT&P’s customers ordered pipe supports for their different projects, they ordered the same type of part over and over. But each time an order was received, PT&P engineers had to do the calculations and manually enter the specifications, even though they had been through the same exercise dozens of times before. This repetitive process was tedious, time-consuming, and increased the likelihood of errors along the way.

Part of the problem arose from the lack of a truly standardized process in the engineering department. Each engineer prepared proposals and fabrication reports using his or her own preferred format. The computer literate engineers generally used a word processor or the Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet program, while those who were not well trained on the computer did their computations manually, with hand calculators. Further delays arose as engineers repeated their calculations to check for accuracy. Under this system, then, the printed formats for part descriptions and reports varied widely among the engineering staff. Such inconsistencies caused confusion and frequently required shop personnel to go back to the engineers for clarification. All of this led to shipping delays and sometimes angered customers.

The lack of network capability made it impossible to centralize or share data, further slowing the process. Since there was no database capability, there were no search tools with which to retrieve data. When clients ordered the same parts again, the engineers had to reenter the data that had been entered previously. All the engineering calculations also had to be done again. This slowed the company’s response to bids and contributed to problems meeting production and delivery deadlines.

Chapter 6: Leading the Industry Into the Next Century

“What we put in here is astounding and we have a good reason to be proud of it,” said Larry Altshuler. “We are the best there is in the industry.” Piping Technology & Products has accomplished a lot during the last twenty years of its history and looking back, there are many reasons for the firm to be proud. Over the years, the people of PT&P have continued to demonstrate the versatility, innovation, and determination that helped them build the firm into a thriving manufacturing business. The company survived strong competition and an industry slump to establish it’s own niche and become one of the world leaders in the manufacture of pipe supports and other piping products. PT&P developed new manufacturing procedures and customized designs that enabled the company to lower costs, improve its products, and compete with better-established rivals. By 1997, PT&P had an impressive record on which to build as the company prepared for an era of international business in the 21st century.

ACQUISITION OF U.S. BELLOWS, INC.

Throughout the company’s history, PT&P has continued to find new ways to diversify its product line. During July 1997, the company further expanded its expansion joints and bellows manufacturing capability through a major equipment acquisition from the Bird Machine Company. PT&P purchased the companies Ketema-US Bellows Division which had been based in Santee, California. The acquisition included the right to use the US Bellows name and ownership of the company’s expansion joint and bellows manufacturing equipment. This included all of the bellows-making machinery, tools, physical assets, and inventory, designs, technical software, historical files, and purchase orders. Also part of the deal were associated copyrights, patents, and licenses, data, catalogues, artwork, customer files, and the marketing materials PT&P would need to provide service to Ketema-US Bellows customers.

In 1995, PT&P had acquired expansion joint manufacturing equipment and know-how from RM Engineered Products. In 1997, the U.S.-Bellows acquisition increased PT&P’s bellows capabilities and also enabled the company to diversify into a new field, the manufacturing of aluminium bellows. Thus, as Piping Technology prepares to begin its second twenty years in the piping industry, the company continues to find new markets in which to compete through a strategy of “intelligent diversification,” that is, expansion into compatible areas of manufacturing.

Chapter 7: Applying the Lessons of the Past in a New Era

During Piping Technology & Products’ third decade in business, the company continued to build upon the foundation of adhering to sound business principles, producing high quality products, and providing outstanding customer service that had made it a success during its first twenty years. Like other companies, PT&P faced its share of challenges including the ups and downs of a dynamic economy. But, PT&P’s founder and president, Durga Agrawal, and his team remained focused on their objective of finding new and better ways to serve their customers. This focus and strong corporate self-discipline enabled PT&P to avoid the common mistakes made by other growing enterprises that expanded too rapidly or acquired unrelated businesses that distracted from the core business.

U.S. Bellows, 1997

The 1997 acquisition of Ketema-U.S. Bellows from Bird Manufacturing, mentioned briefly in the previous chapter, had a significant impact on the ensuing growth and success of PT&P, and is worth revisiting here. The acquisition of Ketema-U.S. Bellows came shortly after PT&P’s 1995 acquisition of another expansion joint manufacturer, RM Manufactured Products. The company joined the two firms together into one wholly-owned subsidiary operating under the U.S. Bellows name.

Since its inception in the 1960s, U.S. Bellows had developed a sterling reputation and was highly regarded in the piping industry. In 1996, Baker Hughes purchased U.S. Bellows and its parent firm, Ketema Process Equipment Company. Baker Hughes then merged U.S. Bellows subsidiary into its Bird Machine Company, which it had acquired in 1989. The plan was to position Bird Machine to compete in new markets with its newly acquired Ketema centrifuges, filters, and other associated products. But Ketema’s U.S. Bellows division did not fit into this business model and thus, Bird decided to close down the bellows division.

Durga Agrawal first learned that Bird was planning to shut down its Ketema-U.S. Bellows expansion joint division around the time that Rick Thompson finished setting up the RM equipment at PT&P’s Houston plant. Taking advantage of his expertise, Agrawal sent a team including Thompson, R.K. Agrawal, and Ben Tatum, PT&P’s longtime plant manager, to California with instructions to assess the condition and value of the Ketema equipment. R.K. Agrawal focused primarily on the electronic materials, customer lists, marketing materials, and the intellectual property, while Tatum and Thompson inspected the machines and other equipment. R.K. later likened this acquisition to being a “kind of fire sale situation” where the management wanted to dispose of the equipment quickly. “I remember going back and forth with them,” said Agrawal. “This was not an auction, so it was not that the company had gone into bankruptcy—it was that they had a parent company who did not want to be in that business anymore.” PT&P agreed to purchase all of the machinery and equipment, along with the U.S. Bellows name. “They had a good name, a good reputation, and I think we did benefit from this acquisition,” said Durga Agrawal. “This was only an asset acquisition—it was not a purchase of the company.” Although PT&P acquired the U.S. Bellows name, it did not buy any liabilities of the company. PT&P only bought the assets: machinery, equipment, inventory, and completion of the jobs in progress, after approval by those customers. The U.S. Bellows subsidiary proved to be a complementary addition to PT&P’s existing product line. Most of the Ketema customers continued to purchase expansion joints from PT&P’s new U.S. Bellows subsidiary, and began buying the company’s engineered products, spring hangers, constant load hangers, snubbers, and other pipe support products. The addition of the new equipment enabled PT&P to increase its expansion joint manufacturing capability beyond what the RM equipment allowed, to produce much larger diameter, custom designed products.

The move into expansion joints and bellows design and manufacturing was one of the most significant moves for PT&P in the company’s entire history. In addition to new product offerings and production capabilities, the acquisition was a catalyst for the physical expansion of the plant and the hiring of new personnel. All of these elements created a demand for more infrastructure in terms of office space, parking areas, and even employee lunch facilities.

New Addition to the Plant

In order to take advantage of the newly acquired equipment and manufacturing capabilities, PT&P had to take several steps to realize the maximum benefit from its new product line. With the acquisition of RM in 1995, PT&P’s recently expanded shop quickly became congested. The company had planned another expansion of the facility, but now had to decide how much additional space they would build. As Durga Agrawal recalled, “After the acquisition of RM in 1995, the machines were kind of congested. We wanted to spread it out so that we could handle material in a more efficient way, and produce bellows at a competitive cost.”

Preliminary planning already was underway to add approximately 50,000 square feet of additional covered space to the shop when PT&P purchased U.S. Bellows. As mentioned earlier, in 1995, the company completed a 100,000-square-foot addition to the plant. In addition to this, employees also utilized a previously existing structure on the site known as the Parker Building. The building was in good condition and had enough room for some foam production (insulated pipe supports) and several offices that had been occupied by the accounting department since it moved from Long Drive in 1998. Still, there simply was not enough covered shop space, a problem that left employees doing some of the material layout alongside the buildings and outdoors, completely exposed to the elements. Now, with all of the U.S. Bellows equipment coming in, and the consequent need for more space for raw materials to feed into those machines, Durga Agrawal faced an important decision. Although the initial plans called for a smaller structure, Agrawal decided to build an additional 100,000 square feet of plant space. The new addition was built over the existing Parker Building and gave PT&P nearly ten acres of total covered workspace at its Holmes Road site.

As in the previous plant expansion, PT&P served as its own general contractor and did some of the fabricating for the project. They hired a firm to erect the steel framework and an electrical company to install the electrical wiring, outlets, and lighting. The new addition provided an opportunity to redesign the flow of the entire main shop. The company extended the overhead crane tracks and could now run the cranes through the entire length of the building. Randy Bailey credits Durga Agrawal with having the foresight to plan beyond the immediate need for space. This decision in turn created a smoother and more efficient flow of production for the PT&P complex. “It wasn’t just about trying to set up U.S. Bellows [in the shop],” said Bailey. “It was actually about moving forward to set up the rest of the shop…to improve the efficiency of the whole plant.” In addition to the new, covered shop space that would encompass bellows manufacturing, assembly, shipping, and the Small and Fast Team, PT&P also added a new lunchroom for employees and additional office space.

Chapter 8: New Opportunities in Electric Power and Engineering

As Piping Technology & Products continued to grow and expand its product line using the equipment obtained by the acquisitions of two leading expansion joint manufacturers in the late 1990s, changes in the electric power generation industry provided unexpected new opportunities that would lead to a greatly enhanced engineering department.

During the late 1990s, many states, including California, began deregulating their electric power industries. The original impetus for this wave of deregulation is found in the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act, passed by Congress in 1978, which set the stage for deregulation and greater competition in the electric power industry by giving non-utility producers of electricity access to wholesale power markets. In 1992, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act, which encouraged greater competition in the bulk power market. In 1996, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued Orders 888 and 889 to “remove impediments to competition in wholesale trade and to bring more efficient, lower cost power to the Nation’s electricity customers.” The directives mandated “open and equal access to jurisdictional utilities’ transmission lines for all electricity producers.” These directives were the final steps making it possible for individual states to restructure the electric power industry, allowing customers direct access to retail power generation. The result of this in many states was the transition of the electric power industry from highly regulated, local monopolies providing a total package of all electric services to a system of competitive companies providing the electricity while the utilities continued to provide transmission and distribution services. States also began moving away from their traditional roles of regulating electricity rates, and toward what could be described as an oversight function of a deregulated electric power industry in which competitive markets would determine prices. This brought about the rise of the independent or merchant power plants.

One of the firms that saw opportunity in the electric power deregulation was a California energy company, Calpine, founded in 1984 by an engineer, Peter Cartwright. With California’s population rising and electricity in increasingly short supply, Calpine, which had been growing steadily since its creation, was poised to take a leading role in this newly formulated, deregulated industry. An electricity crisis in California during 2000–01 added a sense of urgency as power companies tried to meet the increased demand. Consequently, Calpine purchased a large number of gas turbines from General Electric with a plan to construct as many as 100 of the small, efficient, natural gas–fueled merchant power plants, with many of them being located in California. During the spring of 2001, Calpine announced its plans and sent out a request for proposals (RFP) to engineering and construction firms and piping companies. This was a major opportunity for companies who could provide both the engineering and the piping products required for these projects.

The Battle for Calpine

Among the firms responding to the RFP was the Shaw Group, Inc., headquartered in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The Shaw Group was established in 1987 as Shaw Industries, Inc., a pipe fabrication company. During the next ten years, Shaw embarked on a series of expansions including the 1994 acquisition of Fronek Company, Inc. and F.C.I. Pipe Support Sales, Inc. In 1996, Shaw purchased Pipe Shields, Inc., a highly regarded California manufacturer of pre-insulated pipe hanger supports.

During this time, more energy companies began requesting package bids that included the engineering design work and “just-in-time” supply of piping, pipe hangers, and pipe supports. The Shaw Group embarked on an expansion strategy that enabled the company to provide this complete range of services and products for its clients. In time, Shaw developed into one of the world’s largest vertically integrated providers of engineering, construction, manufacturing, and other diverse services, with operations in North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Thus, by 2001, Shaw Group was well positioned when it received the RFP from Calpine to provide the kind of package bid the company requested. As Randy Bailey recalled, “Calpine’s RFP that went out to pipe fabrication shops was for a complete package where they not only wanted the pipe fabricated, they also wanted the engineering design done on the pipe supports and everything married at the same time—done together.” Shaw Group’s earlier acquisition of Fronek and Pipe Shields anticipated these changes in the industry. “They had bought the Fronek group a while back,” said Bailey. “With this pipe support group, they were going to be able to book the Calpine job, they were going to book all this other work, and this is how they could offer a complete package back to the operating companies.”

At the time that Calpine requested bid proposals, a large part of PT&P’s business came from projects related to the petrochemical industry. The company’s management saw the opportunity of getting more involved in electric power plants as something that was doable and potentially very profitable. PT&P began working with Turner Industries, an industrial contractor and fabrication company headquartered in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to submit a proposal to Calpine. Turner would provide the piping, and PT&P would supply the pipe hangers, supports, and other products. Bailey and Agrawal were confident that PT&P could do a better job of providing pipe supports and other products for the Calpine jobs than any other company. Bailey, along with one of the PT&P engineers, joined the Turner representatives and flew to California to meet with Calpine’s top management. After Bailey completed his presentation, he told Ross Cates, one of Calpine’s executives, that while he might get his piping delivered on time by another firm, no one else had the capacity of PT&P to get the large number of pipe hangers, supports, and other products produced and delivered on schedule. Much to the amazement of the astonished Turner Industries representatives, he challenged Cates to visit PT&P’s plant, saying: “Ross, I’ll tell you what. If you are going to go ahead and place this order with them [Fronek], you may as well just open the window, get out on the ledge and jump out. I want you to do one thing…because if you don’t come in and look at our shop and go look at their shop before you make this decision, then I think you are going to regret it.” Cates took up Bailey’s offer and visited both the PT&P plant and Fronek. In the end, Calpine awarded the contract for pipe supports and pipe fabrication to PT&P and Turner Industries.

Chapter 9: Planting Seeds – Building Relationships: Enhancing Quality, Safety, and Customer Services

Throughout the history of PT&P, ensuring that all products met the highest standards of quality has been the core philosophy behind the firm’s corporate culture. As the company acquired its new subsidiaries and doubled the size of its workforce during the years from 2004–2010, it also took several important steps to further enhance its reputation for producing the highest quality piping products, providing good customer service, and improving plant safety for its personnel.

ISO-9001

When PT&P acquired Pipe Shields in 2004, it added a subsidiary that had a sterling reputation in the piping industry and also held the prestigious ISO-9001 certification for quality control. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) establishes international requirements for quality management systems. An ISO-9001 certification signifies that a company’s quality control management system has been measured and approved against a best-practice standard by a third party certification body. The ISO-9001 certification is tantamount to an assurance of quality for customers, a confirmation that the firm has put into practice the required internal processes to meet its stated quality objectives. PT&P had been considering this certification for some time, and the addition of Pipe Shields served as a catalyst in getting the process moving again. Since Pipe Shields relocated to Houston and reorganized as a Texas corporation, the firm’s ISO certification was no longer valid, requiring the new subsidiary to be re-certified. PT&P engaged the services of Det Norske Veritas (DNV), one of the world’s premiere ISO certification agencies, as its third party certification body. DNV, an independent, international foundation, specializes in providing services for managing risk with the goal of protecting life, property, and the environment. It has issued over 70,000 certificates worldwide and provides the most up-to-date management systems certification services for a variety of clients, including many Fortune 500 companies as well as for medium and smaller businesses.

Many customers who ordered products from Pipe Shields had begun requiring ISO certification before accepting bids on new projects. Therefore, PT&P’s management decided to acquire the ISO certification for its Pipe Shields subsidiary, which produced insulated pipe supports. They did not want to lose any of the firm’s previous customers due to the loss of the certification because of the move to Houston, and since they had planned on getting this certification anyway, decided to go through the process for the Pipe Shields subsidiary. Since certification involved a very detailed procedure, they chose to learn the process by certifying one division first, and then go through the certification again later to cover other departments and subsidiaries. PT&P already carried several industry-approved certifications for some of its subsidiaries, including SWECO, which had ASME Section-8 certification, and Anchor Darling, in New Hampshire, which had an N-stamp. The ISO-9001 was the appropriate certification for the company’s Pipe Shields subsidiary and would greatly enhance its quality control credentials.

Rick Moreau, PT&P’s operations manager, had gained experience dealing with the certification procedure for a previous employer. Calling on Moreau’s expertise, PT&P began the certification process after the Fronek acquisitions, but it seemed to gain momentum after the company hired Hank Lippold as quality control manager in March 2006. “We got serious about it with the background I had, and then they brought Hank on board,” said Moreau. “With his involvement, my involvement, and a couple of other people, we were able to get everything ironed out with the ISO program.” With many people contributing to the certification, all of whom had their own ideas and suggestions; it sometimes proved to be a tedious endeavor. The certification program included writing a manual that established quality standards and clearly defined each step of the production process. David Smith recalled that on some days, “we would get in these discussions where everybody was debating which method was best, and we would get sidetracked.” Smith credits Randy Bailey as one who could get the process moving forward again. “We finally came up with something we could live by,” said Smith. “Once we all got on the same page…it was easy.” Hank Lippold recalled that he had been working about one month at PT&P, just long enough to learn his way around, when he became involved in the ongoing ISO program. “We worked on it approximately . . . I am going to say about eight or nine months. We were able to turn around, have our first audit, and get our certification.”

One interesting feature of ISO is that while it has specific elements to its program, it does not dictate how a firm will meet the fundamentals of good quality control. It is up to the individual firm to establish its own quality procedures and record how it will address each of the ISO elements as they relate to its particular industry. Once the company is formally certified, it must follow its own self-identified quality and production standards. As Larry Altshuler explained, with ISO “everything is planned and adhered to. But with this program… if you go to people and you say you are ISO certified, they know the minimum standards they are going to get, which are very high. And it gives you a good feeling when you know you are turning out something that is really darn good all of the time!”

PT&P received its ISO-9001 certification for the “Manufacture of Hot and Cold Pipe Supports” on October 23, 2007, a testimony that “PT&P’s Quality Management System has been certified against the best practice standard and is compliant.” Acquiring the ISO-9001 certification was an important milestone for PT&P. Rick Moreau noted the significance of the new certification, stating that, “it shows customers that you are taking that next step, you are in the upper echelon of fabrication companies.” And David Smith observed that “The big selling point is that some of our customers, especially the overseas clients, will not do business with you unless you are ISO certified.” For PT&P, the new ISO certification proved helpful in that it established written standards that the company’s growing workforce easily could learn and maintain. The extensive, step-by-step documentation ensured that everyone was familiar with those standards. “Quality control is really different in the world as we know it today,” stated Lippold. “It does not mean that you have any better quality than you had before, it is just that they want you to back it up more. So, we spend more time testing and documenting everything we do.”

Chapter 10: Making History and Building Toward a Future

During Piping Technology & Products’ third decade in business, the company continued to build on its previous success, based upon the fundamental business principles of its founder, Durga Agrawal. With this focus on its core values and on its core businesses, PT&P achieved a prominent position as one of the leading firms in the global piping industry. The company became increasingly known for its expertise as a “go-to” resource, for its ability to provide emergency services, and as a one-stop shop for its customers. By 2010, PT&P’s growing prominence in the industry provided opportunities for Agrawal to use his experience as a businessman to help influence public policy and also gave him opportunities to provide support for many charitable and philanthropic endeavors. Agrawal always believed in the concept of putting profits back into his business and in giving back to the community. This adherence to sound business principles and his own personal beliefs helped PT&P achieve a level of success during its third decade that might have seemed unimaginable to the young man from Lakhanpur, India, when he first arrived in Houston in 1969.

By continuing to follow a philosophy of providing the best quality products, giving outstanding customer service, and maintaining a diverse product line, PT&P enjoyed great success during good economic periods and maintained a steady customer base during periods when the economy slumped. With a full array of pipe supports and engineered products and a range of value added services, PT&P developed the ability to shift product lines and quickly became adept at entering new avenues within the industry which significantly broadened the company’s customer base. As Durga Agrawal stated in an interview, “Corporate diversification has always been a priority to us…while many of our competitors failed, we not only survived, but thrived because of our corporate structure.”